With work commencing on an expanded

Javitz Center on New York City's Far West Side, a recently opened

riverfront convention facility in Pittsburgh and other convention centers built or planned in Indianapolis, Minneapolis, Philadelphia and Cleveland, American cities have been racing to capture converging convention populations to revitalize aging city centers. By providing “insta-population” density, elected officials and business leaders hope to boost business at downtown restaurants, shops and hotels and attract a critical mass of people to encourage private investment in the urban core. While the economic benefits of these new and expanded downtown convention centers is debated among urbanists, undoubtedly, these new glass and steel behemoths are swallowing city blocks and imposing enormous, decorated warehouse volumes on pedestrian-scaled streets.

In this week's New Yorker, Paul Goldberger

reviews Massimiliano Fuksas’ design for a new convention center in Milan. (See

A Daily Dose of Architecture for

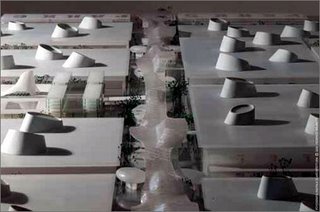

coverage of its opening) The "most exciting convention center in the world," known as Fiera Milano, isn't located anywhere near the Italian city. Instead, the enormous

Milan Trade Fair Complex sits at the site of an old gas refinery near an intersection of highways not far from the Milan airport. This new center, taking advantage of its sprawling

site, is divided into "eight halls, each as large as a medium-sized American convention center... placed on either side of a central axis, an elevated street a mile long." As a result, the structure functions smoothly and efficiently and avoids the problem of overshadowing pedestrian-scaled urbanity. In contrast, designers’ recent response to urban convention centers’ challenges, often sacrifices the flexibility of expansive, uninterrupted exhibit spaces by separating and re-scaling volumes in a futile attempt to lessen the obtrusive presence.

The

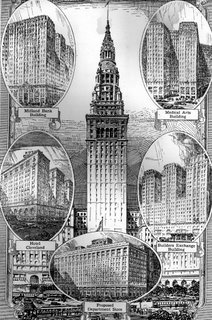

International Exposition Center in Cleveland, with over one million square feet of exhibition space, is one of the largest convention facilities in the world. While its incredible spans can accommodate auto shows, boat shows, and conventions of any size, it fails to offer the significantly more intimate meeting spaces and current comforts and amenities that newer facilities offer. As a result, its location adjacent to Hopkins International Airport has been planned for future airport expansion. The City of Cleveland along with local business leaders have identified the need to replace the aging IX Center with a new urban convention facility in Cleveland’s Downtown core. With a virtual guaranteed site behind Forest City's Tower City complex, continued discussion to attract a

Medical Mart (read this week’s Crain’s Cleveland for an update) to become a critical component of the new project, and years of planning to gain public support and a plan to finance the construction of a brand new structure, Cleveland is likely to abandon the current convention center location south of the city to open a new urban convention facility sometime within the next decade.

“Convention-goers are expected to stay in Milan, and most of them travel to and from the city center via a new underground rail link. The Fiera is only a convention center – not one of those ‘edge-city’ nodes like Tyson’s Corner outside Washington, or the Galleria section of Houston, which try to provide all the elements of a traditional city amid suburban sprawl and end up draining the metropolis to which they are attached. The Fiera has no shopping, no cineplexes, and, for now, no hotels – nothing to fulfill the current mantra of ‘mixed-use’ as the obligation of all large-scale urban-development projects.”

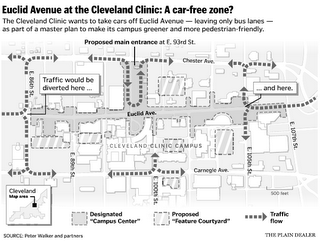

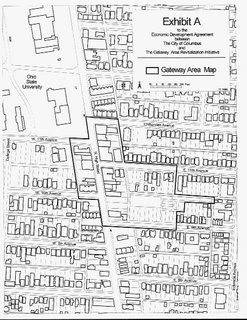

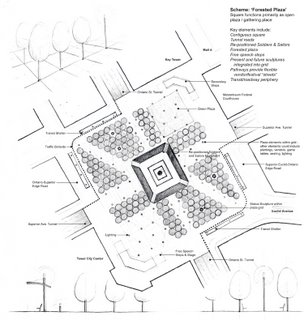

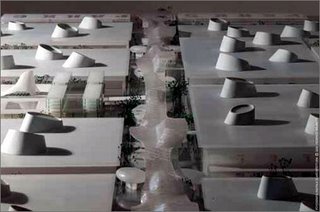

In Cleveland, the anticipated

convention center will complete the unfinished southern end of Tower City Center and sit on a site that cascades from the City streets atop the Downtown bluff to the industrial valley below. Among the final Downtown site selections, this site best avoids an uncomfortable confrontation with existing, more intimate context with a location at the southern edge of Downtown. In addition, it will connect into an already expansive office and entertainment complex, will provide an opportunity to connect truck and auto traffic to major interstates without significant interruption on the Downtown grid, and allow travelers to connect to the region’s airport via rapid transit.

A better opportunity to completely separate the sprawling and ever-changing functions and requirements of this exhibition ‘factory’ from the center city has been lost in the critical need for a revitalized Downtown. A regional convention facility, much like an area airport, does not need to occur at an urban center for the health of its city and metro area. A better-performing convention center and less invasive structure, that can still provide the same opportunity for hotel and restaurant dollars to be used Downtown, would be ideally situated in the way Milan’s Fiera has. Either replacing the existing IX Center and extending the airport rail line or building on a similarly located

site can, like Milan Fiera, allow the convention center to be the best version of a convention center. Committing a convention center for a site which could better be used for hotel, office and retail expansion (located conveniently at Tower City’s rail hub) to serve an outlying facility, will follow the missteps that other American cities have already taken. The result will stifle an opportunity for a plagued urban center to refine its gritty character through organic demand and subsequent growth, by landing the human equivalent of an airport hangar at the heart of a steadily resurging city.